Scientists haven’t quite decoded how animals smell, but researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) found that it’s different from previously thought.

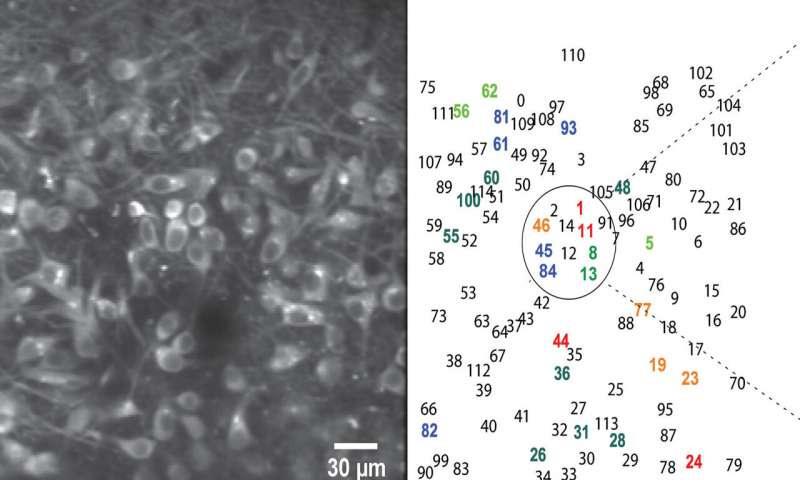

To understand how the brain processes and interprets smells, CSHL neuroscientists Florin Albeanu, Alexei Koulakov and colleagues Honggoo Chae, Daniel Kepple, Walter Bast from CSHL, and Venkatesh Murthy from Harvard University, are putting past odor classifying models to the test, and they’re discovering discrepancies.

Their results, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, differ from other published studies that found predictable relations between molecular properties of odors and activity in the early stages of the olfactory system. The new research found that while there were some correlations between some molecular properties of odors and corresponding neuron activity response, they “held little predictive power when new odor pairs or shuffled properties were tested.”

When it comes to smell, “we don’t really know what the brain is looking for, and we don’t know what physical or chemical features, if any, the brain extracts,” Albeanu said.

Generally, scientists know that odor particles first enter through the nasal cavity, where odorant receptors expressed by olfactory receptor neurons in the sensory tissue bind to them. The olfactory bulb, a structure located in the forebrain of mammals, then processes information sent up from the receptors. Afterwards, the bulb sends out this information to several higher processing brain areas, including the cerebral cortex. There, the olfactory output messages are further analyzed and broadcast across the brain before they’re conveyed back to the bulb in a feedback loop.

“Rich feedback makes the olfactory system somewhat different from the visual system,” Koulakov said. “Olfactory experience is very subjective, perception of smells actually depends on the context, and on an individual’s prior experience.”

Factoring these in, Albeanu and Koulakov said it’s probable that the entry-level of olfactory inputs and the further processed bulb outputs care about different aspects of smell.

The “rather unexpected” results of the new research, Koulakov said, are an exciting opportunity to build a more comprehensive and testable computational model for the odor space that captures the differences in informational relevance for scent features across the various levels of olfactory processing.

This paper is the first discovery to come out since the pair received the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director’s Transformative Research Award for an innovative neuroscience research project on the olfactory system in 2018. Albeanu views these findings as “an opening act” for continued research in this area.

Leave a Comment